January 7, 2024

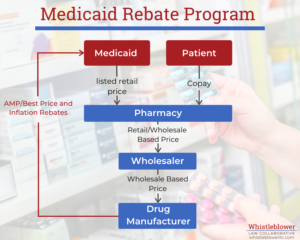

Medicare and Medicaid cannot negotiate drug prices the way private insurers can. This creates a risk that the public will overpay for needed drugs. The Medicare and Medicaid Drug Rebate Programs require manufacturers to pay rebates to Medicare and Medicaid so that they do not overpay for drugs. The programs are complicated. They are also vulnerable to several types of fraud. Below we explain how each program works, as well as ways drug companies can defraud them. We also give examples where the False Claims Act has been used to address fraudulent behavior that harms the programs.

Medicare covers prescription drug costs for beneficiaries covered under Medicare Part D. In addition, it covers specific outpatient prescription drugs for those with Medicare Part B. Similarly, Medicaid covers prescription outpatient drug costs for qualifying individuals with financial need. Currently, Government insurers are unable to negotiate drug prices with drug manufacturers. This creates a risk that drug manufacturers will force Medicare and Medicaid to pay above-market prices for drugs.

In 1990, Congress enacted the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP) to ensure Medicaid does not overpay for drugs compared to private purchasers. Under the program, a drug manufacturer must pay quarterly rebates to state Medicaid programs in exchange for Medicaid’s coverage of the manufacturer’s drug. Currently, around 780 drug manufacturers participate in this program. In 2022, the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program returned nearly $48.5 billion to the government.

In 2022, President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 into law. It created a similar program: the Medicare Prescription Drug Inflation Rebate Program (MPDIRP). The MPDIRP was created to ensure Medicare and its beneficiaries do not overpay for drugs compared to their privately insured peers.

The goal of the MDRP is to return to the states the difference between the best price that a manufacturer sells a drug for and the market average. This is to make sure that Medicaid gets the best deal of any wholesale buyer. It does so by requiring manufacturers first to calculate the average price and best price for which they sold each drug. Then, they must refund the difference to Medicaid each quarter.

To really understand how the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program formulas work, one first needs to understand some key terms.

The AMP is the average price buyers pay for the drug over the past quarter. This price should include discounts given to purchasers such as retail pharmacies but does not include service fees. Manufacturers must calculate this price every quarter from their sales and report it to the government.

The Best Price is the lowest price that a purchaser has paid the manufacturer for the drug including cash discounts, rebates or any other inducement given to private customers.

Typically, the rebate consists of two parts: a fixed basic rebate and an inflationary component.

Under the MDRP, state Medicaid programs receive a different basic rebate for branded drugs, generics and certain pediatric and blood clotting drugs.

Basic rebates for brand name drugs are calculated as the larger of the difference between AMP and the Best Price or 23.1% of the AMP.

The basic rebate for certain pediatric and blood clotting drugs Is 17.1% AMP.

The basic rebate for generic drugs is 13% of the AMP and there is no best price provision.

The additional rebate is meant to offset any drug price increase beyond inflation. It is calculated based on the increase in a drug’s price from when it first entered the market, or in 1990, whichever is later. If this increase is larger than the increase in the Consumer Price Index for Urban areas over the same period, the manufacturer must rebate the difference to the states.

This has actually become a major driver of Medicaid Drug Rebates. A 2015 HHS-OIG report found that most brand drug rebates in 2012 were attributable to the inflationary component rebates.

The Medicare Drug Rebate Program is similar to the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. It too requires calculations based on accurate reporting of a drug’s AMP. The rebate calculation is complicated and varies based on whether the drug is covered under Medicare Part B or Part D. Additionally, the rebate amount will differ if the drug is currently on an FDA shortage list. Failure to timely remit the rebate may subject the manufacturer to a penalty equal to 125 percent of the rebate amount.

A key difference between the programs is that, unlike Medicaid (which is prohibited from negotiating prices with drug manufacturers), the Medicare program requires drug manufacturers to negotiate with the government for certain drugs. In August 2023, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the first 10 drugs to be subject to price negotiations. However, any negotiated prices will not become effective until 2026. In the meantime, pharmaceutical manufacturers are challenging the Inflation Reduction Act’s drug pricing negotiation provisions in court.

Drug manufacturers sometimes try to manipulate the AMP or the Best Price to reduce their rebate. Drug manufacturers may also try to misrepresent the brand/generic status of a drug to lower their quarterly rebate.

Pharmaceutical companies sometimes will underreport the AMP. Because the rebates are a percentage of AMP or AMP minus best price, a lower reported AMP reduces rebates to state Medicaid programs.

Companies have found many ways to try to reduce their rebate obligations, including offering unreported discounts to private companies (but not Medicaid or Medicare) or using fees to reduce the reported AMP.

In 2018, AstraZeneca paid $46.5 million to settle a False Claims Act suit involving AMP fraud. According to the Department of Justice, AstraZeneca included fees paid to wholesalers when calculating the quarterly AMP. As a result, AstraZeneca artificially reduced the AMP and underpaid quarterly basic rebates due to state Medicaid programs.

Pharmaceutical companies may also fraudulently inflate the Best Price of the drug. Since the Medicaid brand drug rebate includes the difference between AMP and Best Price, the higher the Best Price of the drug, the lower the rebate will be.

In 2008, Merck & Company paid $650 million in part to settle a False Claims Act case alleging fraud of this sort. The Department of Justice and state Attorneys General alleged that Merck did not report the price offered to hospitals for using its drug Pepcid. Thus, the Best Price that drug manufacturers reported to state Medicaid programs was considerably higher than the price hospitals were paying to access the drug. This fraudulently reduced Merck’s quarterly rebate.

Pharmaceutical companies may misrepresent whether a drug is a generic or a brand name drug. As noted above, the Medicaid rebates for generic drugs are generally about 10% lower than for brand drugs.

A good example of this type of fraud is our client’s False Claims Act lawsuit against Mylan. Mylan paid the United States and States $465 million in the largest False Claims Act settlement of 2017.

Mylan misclassified the EpiPen as a generic drug rather than a brand name drug. Since the EpiPen had no therapeutic alternatives available, Mylan was able to charge incredibly high prices on the private market for the EpiPen. However, misclassifying the EpiPen as a generic drug to Medicaid allowed Mylan to pay only 17% of AMP instead of AMP minus Best Price. As a result, even though the EpiPen price increased at a rate much faster than inflation, Mylan did not have to pay a large additional rebate to offset those price increases. This is because the rebate formula differs for brand name and generic drugs.

Because the inflationary rebate component becomes so significant when drug manufacturers dramatically increase their prices, they may seek to fraudulently avoid this rebate component. One example of this is misleading the government regarding the initial price of the drug (called the base AMP).

One of our clients blew the whistle on inflationary component fraud in a False Claims Act case against Mallinckrodt ARD. The case, which was captioned United States ex rel. James Landolt v. Mallinckrodt ARD LLC, 1:18-cv-11931-PBS (D.Mass), involved the drug Acthar. Our client alleged that Mallinckrodt ARD improperly used a base AMP from 2010 for its high-priced drug Acthar. Acthar first entered the market in the 1950s, so its base AMP should have been calculated from 1990. From 1990 to 2010, Acthar’s price dramatically outpaced inflation. Reporting a later base AMP resulted in Mallinckrodt paying additional rebates only on price increases after 2010. This reduced the additional rebate owed to Medicaid by hundreds of millions of dollars. In 2022, Mallinckrodt ARD agreed to pay $234 million in settlement of the allegations.

The Medicare and Medicaid Drug Rebate Programs rely on drug manufacturers to accurately report prices. When manufacturers cheat in an attempt to lessen Medicare and Medicaid rebates, the False Claims Act comes into play. The False Claims Act creates liability for anyone who submits false or fraudulent claims to the government.

The False Claims Act also forbids reverse false claims. In reverse false claims, liability arises because a company retains money owed to the government (by, for example, underpaying drug rebates). The False Claims Act is critical to fighting fraud against the Medicare and Medicaid Drug Rebate Programs.

Whistleblowers are crucial to bringing fraudulent rebate schemes to light. If you know of violations of the Medicare or Medicaid Drug Rebate Programs, contact us for a confidential consultation.